The power of telling our own stories

When we as Africans tell our own stories, we re-write the stories in the history books that our children are still taught in schools.

In November 2018, the South African fast-food chain Chicken Licken launched a new ad campaign. “A long long time ago, when leather was still in fashion, a young man left his home to satisfy his hunger for adventure…” begins the opening line of the “Legend of Big John.” It tells the story of an African man who in the 17th century discovers a foreign land and names it Europe. A month after its release, the ad was banned by the South African Advertising Regulatory Board who ruled that colonization is “not open for humorous exploitation” and that the ad “trivializes an issue that is triggering and upsetting for many South African people.” If you haven’t seen the ad, watch it now before continuing.

I find it not only hilarious but also subversive. I especially like the part where the white woman at the end gives Big Mjohnana, the young man of the legend, the eye. Perhaps that is what did it for the regulators. We all know that white men have always been sensitive about “the black mandingo.”

I fully agree with commentator Zama Mdoda when he writes:

The ad didn’t seek to make light of colonization or the trauma it inflicted (and still inflicts). If anything, it depicts an unrepresented version of the African, one with agency and adventure compared to the unwilling victims of a colossal system of exploitation. It’s also tea-worthy commentary on the absurdity found in the notion that a person can discover a land with people already living there, which I consider a hearty f*** you to Christopher Columbus.

When we as Africans tell our own stories, we re-write the stories in the history books that our children are still taught in schools. We do what Edward Said wrote about decades ago in his seminal work, Orientalism, and move from being objects to becoming subjects of our stories. And when it comes in the form of “reimagined” legends, folktales and myths, as this ad has done, we reclaim some of that history.

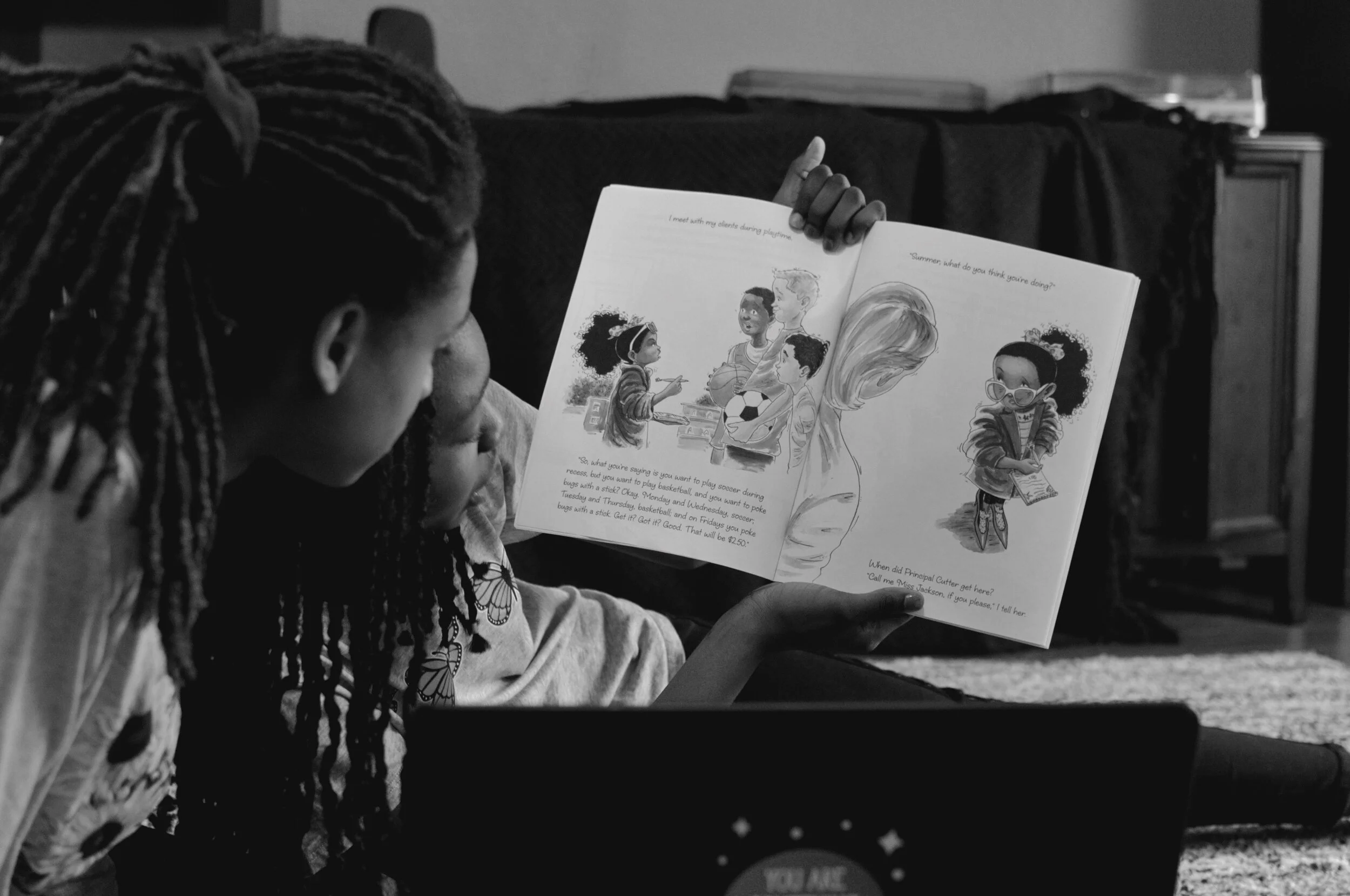

In 2018, I edited an anthology of Re-Imagined Folktales from Africa entitled Story Story, Story Come. The collection of 12 tales by writers from eight African countries seeks to do what Grant de Sousa, the director of the Chicken Licken ad, has done with the Legend of Big John—tell stories from an African perspective. Speaking at the launch of the ad, De Sousa said, “The beginning of my treatment was this painting which we had all seen in textbooks here. It was this insane depiction of these glorified Europeans, namely the Dutch, rocking up on the shores of South Africa, and ‘rescuing’ these poor African villagers.”

Image: Ilona Virgin

In Story Story, Story Come, one author uses the site of real archeological carvings of giraffes in Niger as the inspiration for her story in which a little girl imagines how they got there and whether they will still be there for generations to come as we continue to destroy our planet. In another tale from Zambia, a young blind girl called Iketeñi restores the blind King’s eyesight through her bravery, subverting the idea that young girls and people living with disability cannot be heroes in stories and in real life. One of my favorite characters is Ma’Dlovu, who saves her community from starvation with the help of a talking mushroom (which also happens to be a reincarnation of Thomas Sankara), and in the process leaves her useless drunkard of a husband who hangs out with people who “buy him drinks but do nothing to help him succeed.” We all know people like that!

Some of the stories tackle themes recurrent in traditional folktales, such as greed. For example, we find out Why Chickens Cannot Fly. It is because Chicken, after being named King of the Skies because his comb resembles a crown, squanders all the birds’ wealth on gold and many wives, and is condemned to a lifetime on the ground. Others, notably The Big Nest from South Sudan is a powerful tale about how war destroys families and the very glue that keeps communities together. What they all have in common is that they speak to issues that we face today as Africans. Without censorship.

The ban of the Chicken Licken ad is testament to the fact that we need to control our means of production and distribution. The publishers of the anthology, Zukiswa Wanner and Lola Shoneyin are African women. The illustrator, layout designer, and I, the editor, are all African women. Who is telling the story, who is editing it, who is turning words into images, and who is publishing it matters just as much as the story itself. And I am proud to say that the Story Story, Story Come anthology is truly ours.

Maïmouna Jallow from Africa Is a Country